SPOT the signs

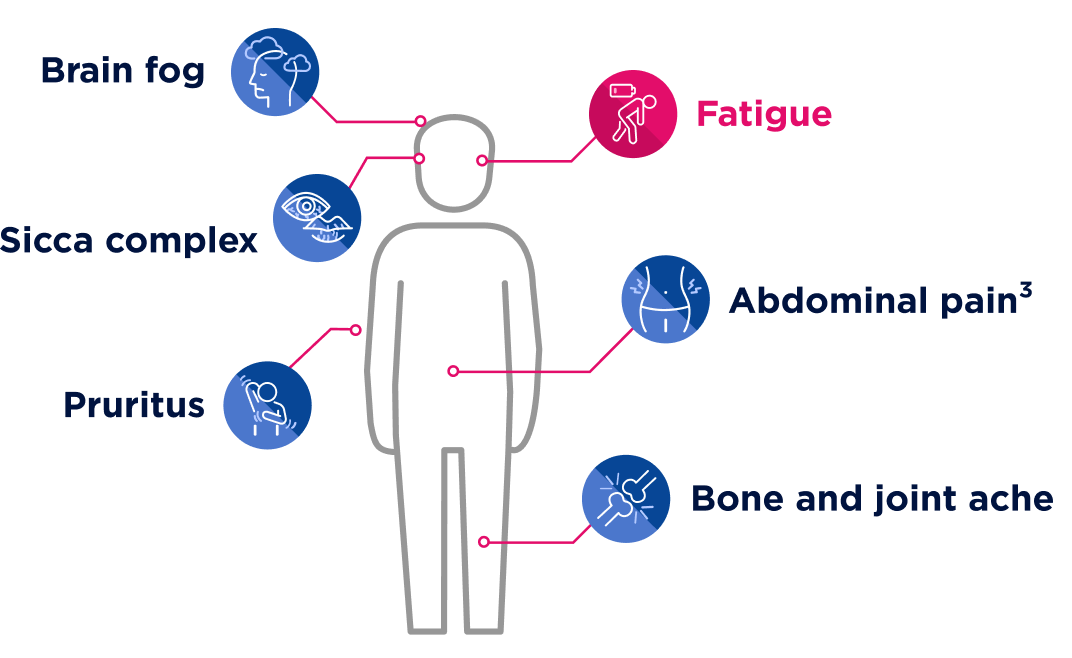

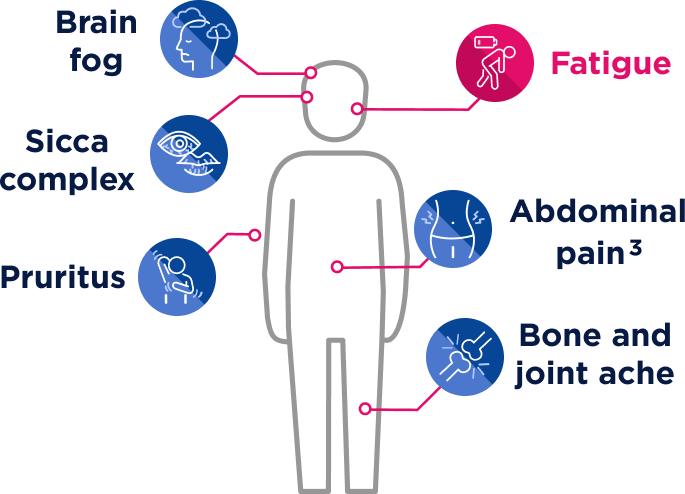

PBC presentation and progression are unique to each patient1,2

Some patients may be asymptomatic or present with one or a combination of the following manifestations throughout the course of the disease1,2:

Understanding fatigue

Fatigue is the most common symptom of PBC3

Described as a feeling of severe exhaustion that doesn’t seem to go away, PBC-related fatigue is often associated with3-5:

- Physical weakness

- Unrefreshing sleep

- Mental cloudiness

- Low motivation

- Physical weakness

- Mental cloudiness

- Unrefreshing sleep

- Low motivation

Fatigue can present independently of pruritus and should be evaluated separately.6

To maximize the impact on patients’ lives, treatment goals should encompass biochemical control and the impact of symptoms like fatigue on their daily activities.7

Fatigue affects up to 78% of patients.3

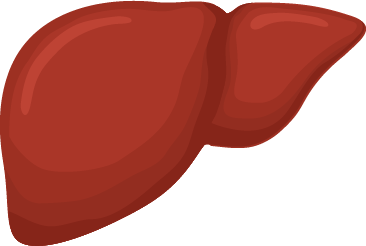

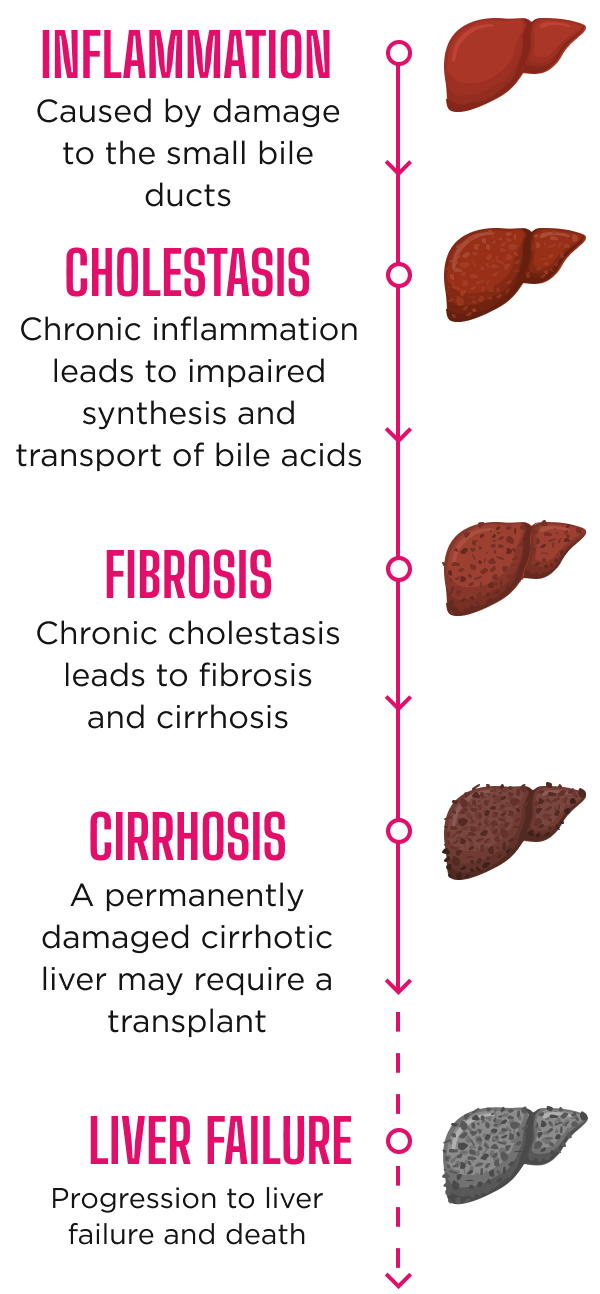

Disease progression in PBC8

Inflammation

Caused by damage to

the small bile ducts

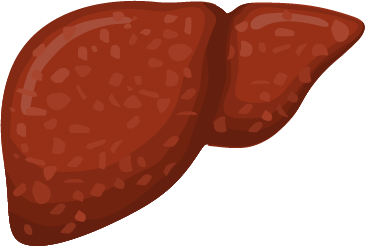

Cholestasis

Chronic inflammation leads to impaired synthesis and transport of bile acids

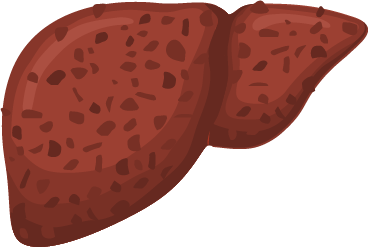

Fibrosis

Chronic cholestasis leads

to fibrosis and cirrhosis

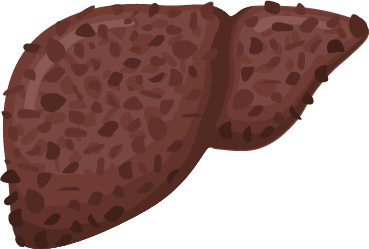

Cirrhosis

A permanently damaged

cirrhotic liver may

require a transplant

Liver failure

Progression to liver failure and death

Disease progression in PBC8

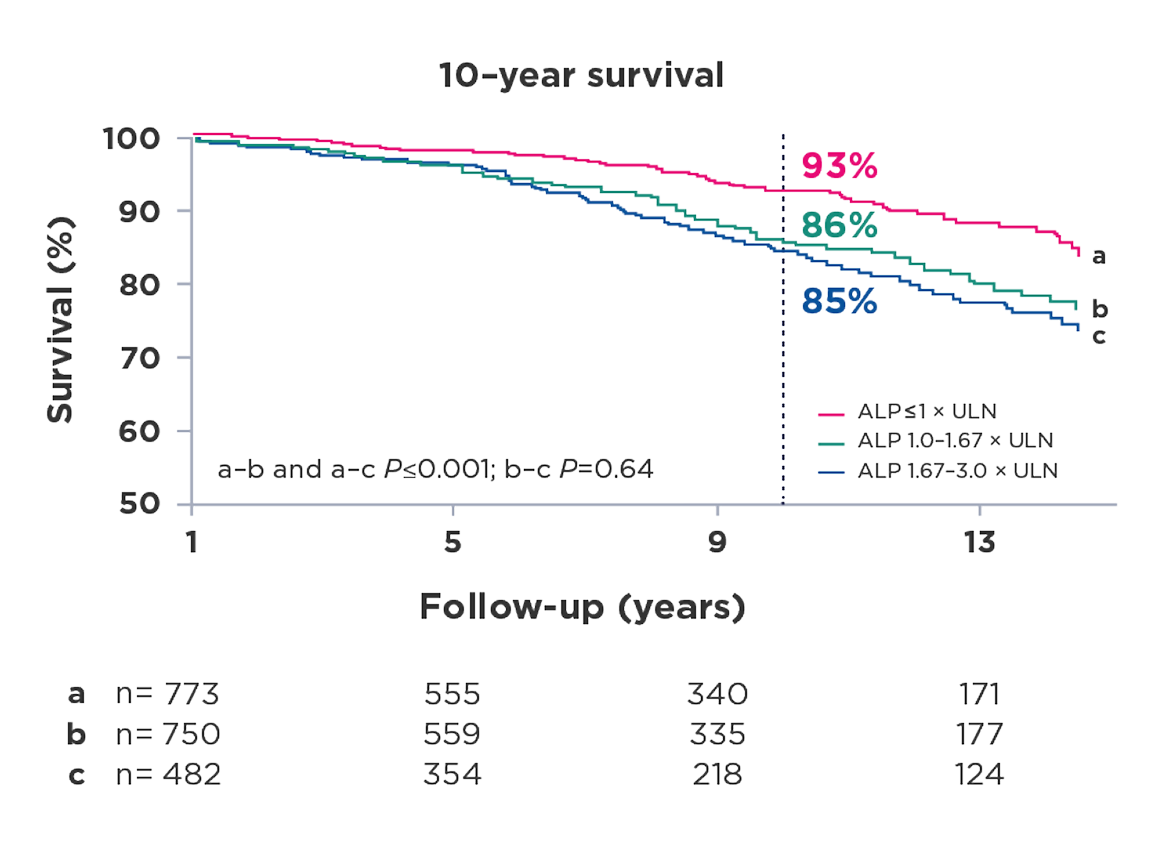

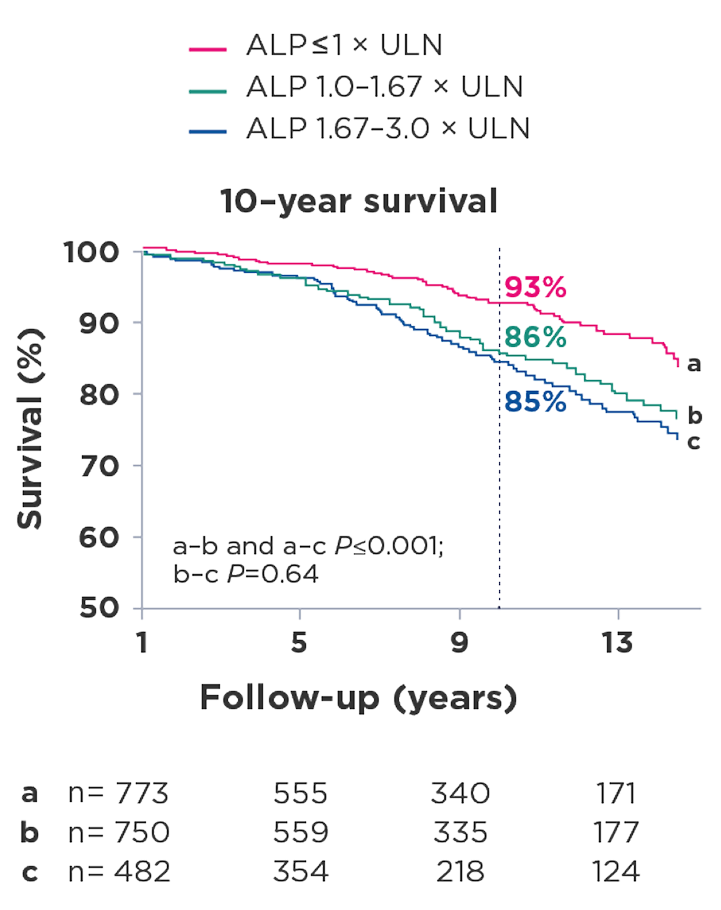

Liver biomarkers correlate with outcomes and disease progression9-12

Elevated liver biomarkers, notably ALP, are key indicators for assessing disease severity, tracking progression, and evaluating treatment response in patients with PBC.9

The extent of ALP and total bilirubin thresholds diverging from normal can predict liver transplantation or death in patients with PBC.10-12

Survival estimates stratified by ALP levels in patients with normal bilirubin at 1 year10

Adapted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.: Murillo Perez CF, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Goals of treatment for improved survival in primary biliary cholangitis: treatment target should be bilirubin within the normal range and normalization of alkaline phosphatase. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(7):1066-1074, suppl. https://journals.lww.com/ajg/abstract/2020/07000/goals_of_treatment_for_improved_survival_in.20.aspx

Achievement of normal ALP is associated with improved survival.10

Adapted with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.: Murillo Perez CF, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Goals of treatment for improved survival in primary biliary cholangitis: treatment target should be bilirubin within the normal range and normalization of alkaline phosphatase. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(7):1066-1074, suppl. https://journals.lww.com/ajg/abstract/2020/07000/goals_of_treatment_for_improved_survival_in.20.aspx

PBC can lead to permanent liver damage.12

46% of patients with early-stage PBC progress to intermediate disease within 5 years.9

MAP the route

Consistent monitoring is key to a proactive treatment plan8,13

All patients need frequent assessment of their biochemical response, disease progression, and symptom impact.8,13

Biochemical response to treatment is the key prognostic measure used to assess the risk and speed of disease progression.11,14-16

In order to support your patients along their treatment journey, consider the following:

EVALUATE

at 6 months

Consider evaluating response to treatment every 6 months, at which time changes can be implemented to help slow disease progression.12

MONITOR

ALP levels

Elevated ALP levels are associated with disease progression and can be measured to assess treatment response.4,11,18

CONSIDER

the full impact

Discussing symptoms with your patients can help ensure treatment aligns with their goals and experiences.3,8

Fatigue often goes underreported in patients with PBC.6 Proactively address fatigue with your patients and ask about it directly.

Patients receiving UDCA often continue to experience persistent fatigue. 3,8,19

- Fatigue is largely independent of biochemical disease control3,8,19

- Even patients with early-stage or otherwise well-controlled PBC can experience profound fatigue3

Discussing the impact of symptoms can help in selecting a treatment that supports a patient’s treatment goals.19 PBC-related fatigue can impact your patients through 2 primary components20:

- Central fatigue affects motivation, cognition, and concentration

- Peripheral fatigue involves reduced activity levels, delayed recovery, and decline in muscle function

EVALUATE

at 6 months

Consider evaluating response to treatment every 6 months, at which time changes can be implemented to help slow disease progression.17

MONITOR

ALP levels

Elevated ALP levels are associated with disease progression and can be measured to assess treatment response.3,11,18

CONSIDER

the full impact

Discussing symptoms with your patients can help ensure treatment aligns with their goals and experiences.3,8

Fatigue often goes underreported in patients with PBC.6 Proactively address fatigue with your patients and ask about it directly.

Patients receiving UDCA often continue to experience persistent fatigue.3,8,19

- Fatigue is largely independent of biochemical disease control3,8,19

- Even patients with early-stage or otherwise well-controlled PBC can experience profound fatigue3

Discussing the impact of symptoms can help in selecting a treatment that supports a patient’s treatment goals.19 PBC-related fatigue can impact your patients through 2 primary components20:

- Central fatigue affects motivation, cognition, and concentration

- Peripheral fatigue involves reduced activity levels, delayed recovery, and decline in muscle function

Recognize patients with inadequate treatment response

Inadequate biochemical response

- ALP levels above 1.67 x ULN are correlated with higher risk of negative outcomes17

- Treatment goals include rapid and sustained reduction in ALP levels, ALP normalization, and normal total bilirubin levels3

Continued symptom presentation and impact

- Some patients may experience worsening symptoms, despite biochemical control6,8

- Patients with PBC who experience fatigue exhibit significantly worse overall well-being compared to those without fatigue, severely impacting their quality of life—affecting relationships and impairing mental health5,19

The burden of PBC-related fatigue

Patients with PBC who experience fatigue exhibit significantly worse overall well-being compared to those without fatigue,severely impacting quality of life. The burden of fatigue extends to virtually all facets of life, limiting patients’ ability to be physically active and socially engaged.16,18

When people with PBC experience persistent fatigue, it often prevents them from participating in social events, fulfilling family roles, and performing at work—impacting relationships and impairing mental health16

Patients who respond to treatment may still be at risk of disease progression. Early initiation of therapy is critical to help prevent further damage.18

Inadequate treatment response can lead to cirrhosis, liver transplant, or death. A proactive treatment plan consisting of personalized, collaborative treatment and closer monitoring may be beneficial for some patients.8,13

Up to 50% of patients treated with UDCA do not adequately respond, putting them at risk of progression. UDCA does not alleviate fatigue in PBC, so many patients continue to experience persistent PBC-related fatigue.15,18,19

Up to 50% of patients treated

with UDCA do not adequately

respond, putting them at risk of

progression. UDCA does not alleviate fatigue in PBC, so many patients continue to experience persistent PBC-related fatigue.15,18,19

LEAD the way

Consider patients who may be at higher risk

Certain patients may be at risk of disease progression, inadequate treatment response, and poorer outcomes.8

Risk factors include:

Age: Patients diagnosed with PBC before age 45 are at risk of severe disease with a poorer response to treatment, putting them at higher risk of liver transplant or death.8,18,21

Sex: Males with PBC are at higher risk of disease progression and poorer outcomes largely due to delayed diagnosis. 47% of men with PBC are at moderate or advanced disease stage when UDCA treatment is initiated.8,22

Ethnicity/race: Hispanic ethnicity is a predictor of poor response to UDCA.23 Black patients have a 47% increased risk of death compared to White patients.24

High-risk patient types require a personalized treatment plan and, in some cases, earlier consideration of additional treatment.25

Uncover patients who could benefit from additional treatment

Kim

Kim is a high-risk patient on first-line therapy. Her labs show elevated ALP levels after 6 months on treatment, but she has not been scheduled for a follow-up assessment.

Symptom: Fatigue

Betty

After discontinuing second-line therapy due to tolerability concerns, Betty's bilirubin levels have begun to rise and she is at risk of disease progression.

Symptoms: Fatigue and treatment-emergent pruritus

Miranda

Despite being on first-line therapy for 10 years, Miranda is now showing signs of disease progression with rising ALP.

Symptom: Brain fog

Uncover patients who could benefit from additional treatment

Assess fatigue and its impact on your patients

Taking steps to manage PBC-related fatigue can help improve the quality of life of patients with PBC.19

Effectively identify patients that need reassessment

Frequent monitoring based on evolving guidance can help identify signs of progression and is an important part of a proactive treatment plan.3

Routine monitoring

A 3-month routine monitoring cadence is advised based on AASLD guidelines.3

- An EHR or EMR database can be used to identify patients who may need evaluation or who may require adjustments to their routine monitoring schedule8

- Questions from the PBC-40—the only validated and disease-specific measurement widely used to assess PBC-related fatigue—may be helpful in discussions with patients

- For example, how often in the past 4 weeks did you feel so tired that you had to force yourself to do the things you needed to do? How often did you have to sleep during the day?

- Contacting patients for follow-up may help engage patients who have not been assessed in the previous 12 months

ICD-10 codes

Patients who require a PBC treatment plan may fall under a variety of ICD-10 codes.8,26 When reviewing patient records, consider:

- K74.3 (PBC)

- R74.8 (elevated ALP)

- K74.5 (biliary cirrhosis)

- K83.0 (cholangitis)

- L.29.9 (pruritus)

Help identify PBC patients in your practice

Discover an FDA-

approved treatment

option for adults

with PBC

SIGN up

AASLD=American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; ALP=alkaline phosphatase; EHR=electronic health record; EMR=electronic medical record; ICD-10=International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; PBC=primary biliary cholangitis; UDCA=ursodeoxycholic acid; ULN=upper limit of normal.

References: 1. Younossi ZM, Bernstein D, Shiffman ML, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary biliary cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(1):48-63. 2. Rice S, Albani V, Minos D, et al; UK-PBC Consortium. Effects of primary biliary cholangitis on quality of life and health care costs in the United Kingdom. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(4):768-776.e10. 3. Lindor KD, Bowlus CL, Boyer J, et al. Primary biliary cholangitis: 2018 practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69(1):394-419. 4. Lynch EN, Campani C, Innocenti T, et al. Understanding fatigue in primary biliary cholangitis: from pathophysiology to treatment perspectives. World J Hepatol. 2022;14(6):1111-1119. 5. Younossi ZM, Kremer AE, Swain MG, et al. Assessment of fatigue and its impact in chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2024;81(4):726-742. 6. Koc OM, Toussaint A-K, Untas A, et al. Fatigue in people with primary biliary cholangitis: a position paper from the European Reference Network for Rare Liver Diseases. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online October 10, 2025. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(25)00257-2 7. Levy C, Bowlus CL. Primary biliary cholangitis: personalizing second-line therapies. Hepatology. 2025;82(4):895-910. 8. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: the diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2017;67(1):145-172. 9. Gatselis NK, Goet JC, Zachou K, et al; Global Primary Biliary Cholangitis Study Group. Factors associated with progression and outcomes of early stage primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(3):684-692. 10. Murillo Perez CF, Harms MH, Lindor KD, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Goals of treatment for improved survival in primary biliary cholangitis: treatment target should be bilirubin within the normal range and normalization of alkaline phosphatase. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(7):1066-1074, suppl. 11. Lammers WJ, van Buuren HR, Hirschfield GM, et al. Levels of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin are surrogate end points of outcomes of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: an international follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1338-1349.e15. 12. Murillo Perez CF, Ioannou S, Hassanally I, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Optimizing therapy in primary biliary cholangitis: alkaline phosphatase at six months identifies one-year non-responders and predicts survival. Liver Int. 2023;43(7):1497-1506. 13. Hirschfield GM, Dyson JK, Alexander GJM, et al. The British Society of Gastroenterology/UK-PBC primary biliary cholangitis treatment and management guidelines. Gut. 2018;67(9):1568-1594. 14. Corpechot C, Heurgue A, Tanne F, et al. Non-invasive diagnosis and follow-up of primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46(1):101770. 15. Montano-Loza AJ, Corpechot C. Definition and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis and an incomplete response to therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(11):2241-2251.e1. 16. Samur S, Klebanoff M, Banken R, et al. Long-term clinical impact and cost-effectiveness of obeticholic acid for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis. Hepatology. 2017;65(3):920-928. 17. Kowdley KV, Bowlus CL, Levy C, et al. Application of the latest advances in evidence-based medicine in primary biliary cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023;118(2):232-242. 18. Hirschfield GM, Chazouillères O, Cortez-Pinto H, et al. A consensus integrated care pathway for patients with primary biliary cholangitis: a guideline-based approach to clinical care of patients. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(8):929-939. 19. Khanna A, Hegade VS, Jones DE. Management of fatigue in primary biliary cholangitis. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2019;18(2):127-133. 20. Faisal A. Understanding fatigue and pruritus in primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2024;23:e0216. 21. Carbone M, Mells GF, Pells G, et al. Sex and age are determinants of the clinical phenotype of primary biliary cirrhosis and response to ursodeoxycholic acid. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(3):560-569.e7. 22. Cheung AC, Lammers WJ, Murillo Perez CF, et al; Global PBC Study Group. Effects of age and sex of response to ursodeoxycholic acid and transplant-free survival in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(10):2076-2084.e2. 23. Levy C, Naik J, Giordano C, et al. Hispanics with primary biliary cirrhosis are more likely to have features of autoimmune hepatitis and reduced response to ursodeoxycholic acid than non-Hispanics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(8):1398-1405. 24. Adejumo AC, Akhtar DH, Dennis BB, et al. Gender and racial differences in hospitalizations for primary biliary cholangitis in the USA. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(5):1461-1476. 25. Levy C, Manns M, Hirschfield G. New treatment paradigms in primary biliary cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(8):2076-2087. 26. 2026 ICD-10-CM codes. ICD10Data.com. Accessed November 12, 2025. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes